Aacapella

Learn to read

using AAC

research-based AAC reading system

coming to your iPad

coming to your ipad

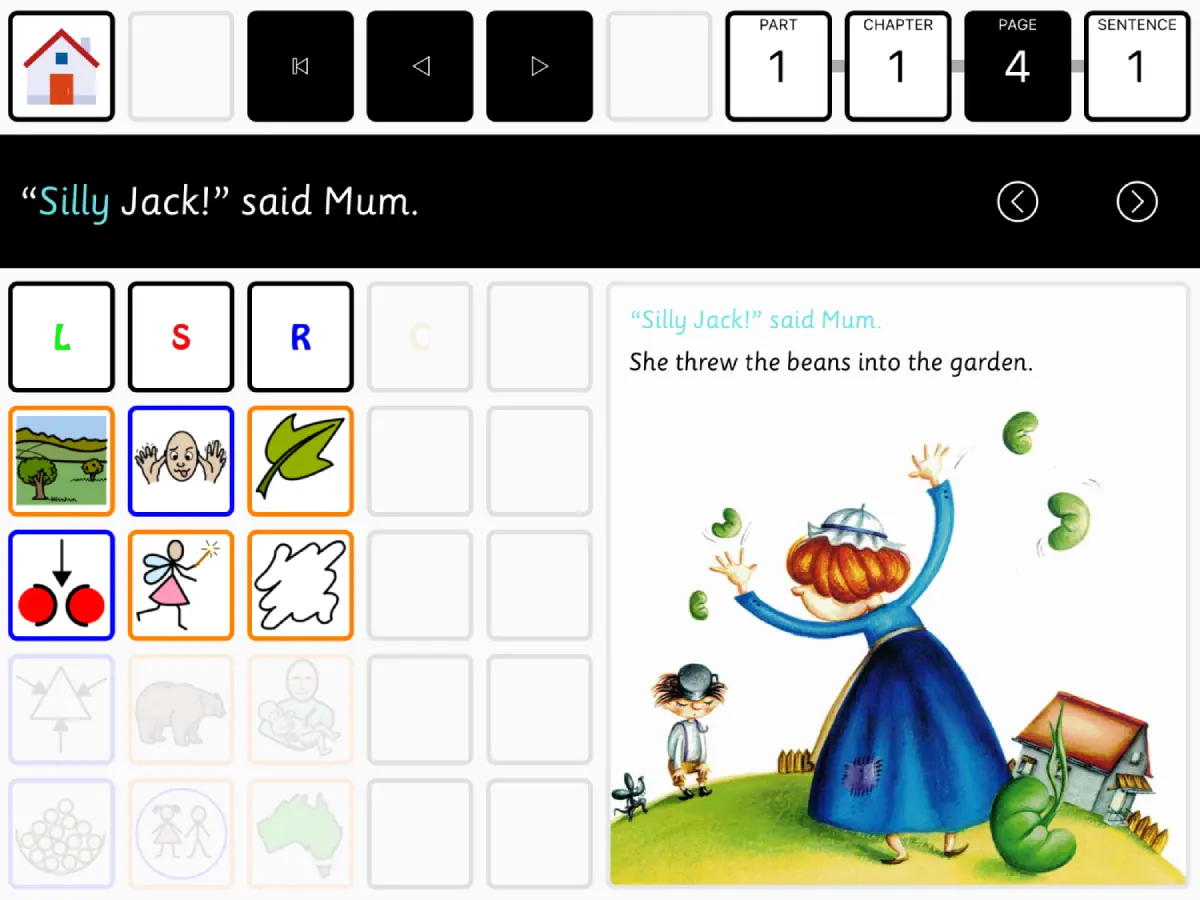

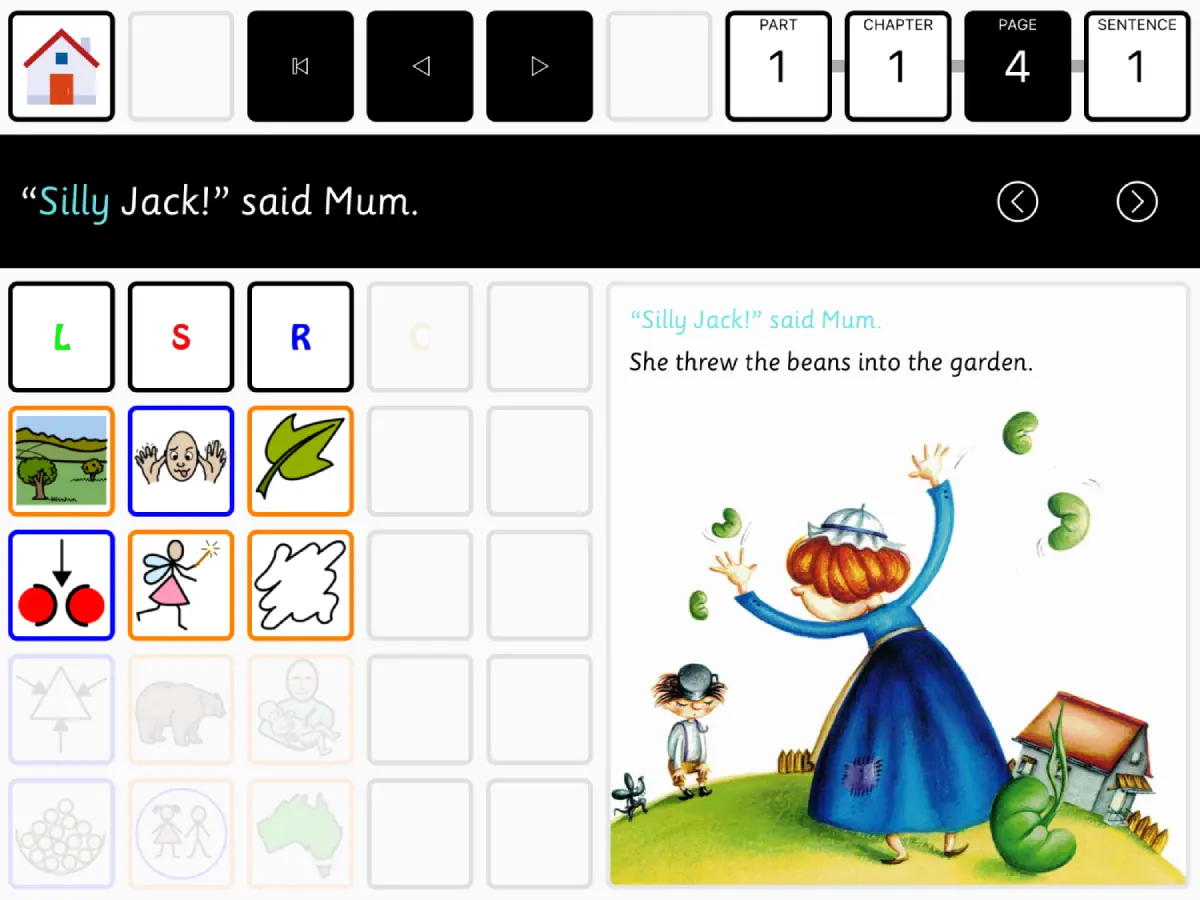

how it works

a reading system that grows with you

participatein shared-bookreading

any iPad with iOS 15 or later

choose yoursymbol set

sounds outunfamiliar words

choose yourvoice

learn to read using mainstream books readers and plays

learn todecode

direct access withoptional keyguard

and switch accesscoming in a later release

read aloudindependently

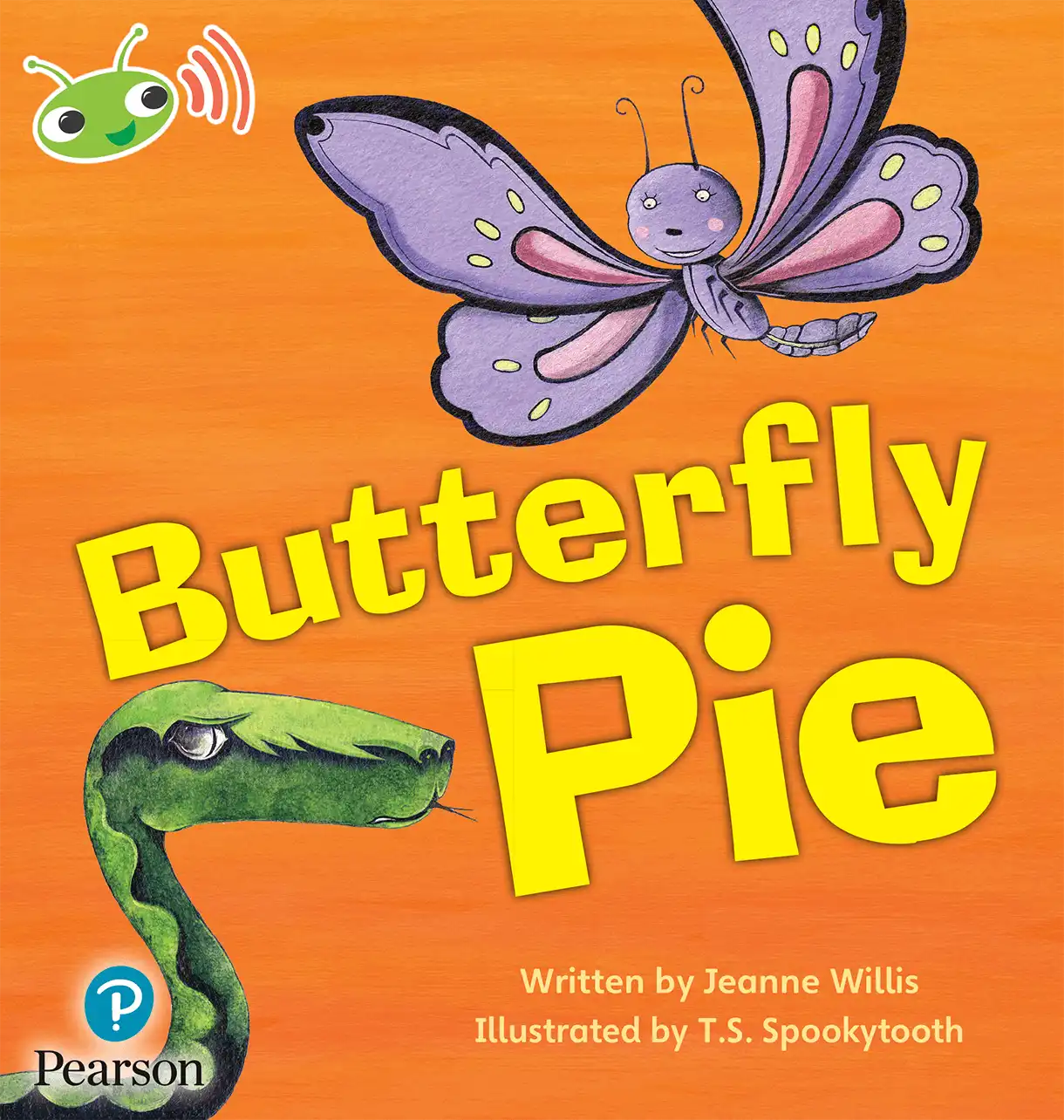

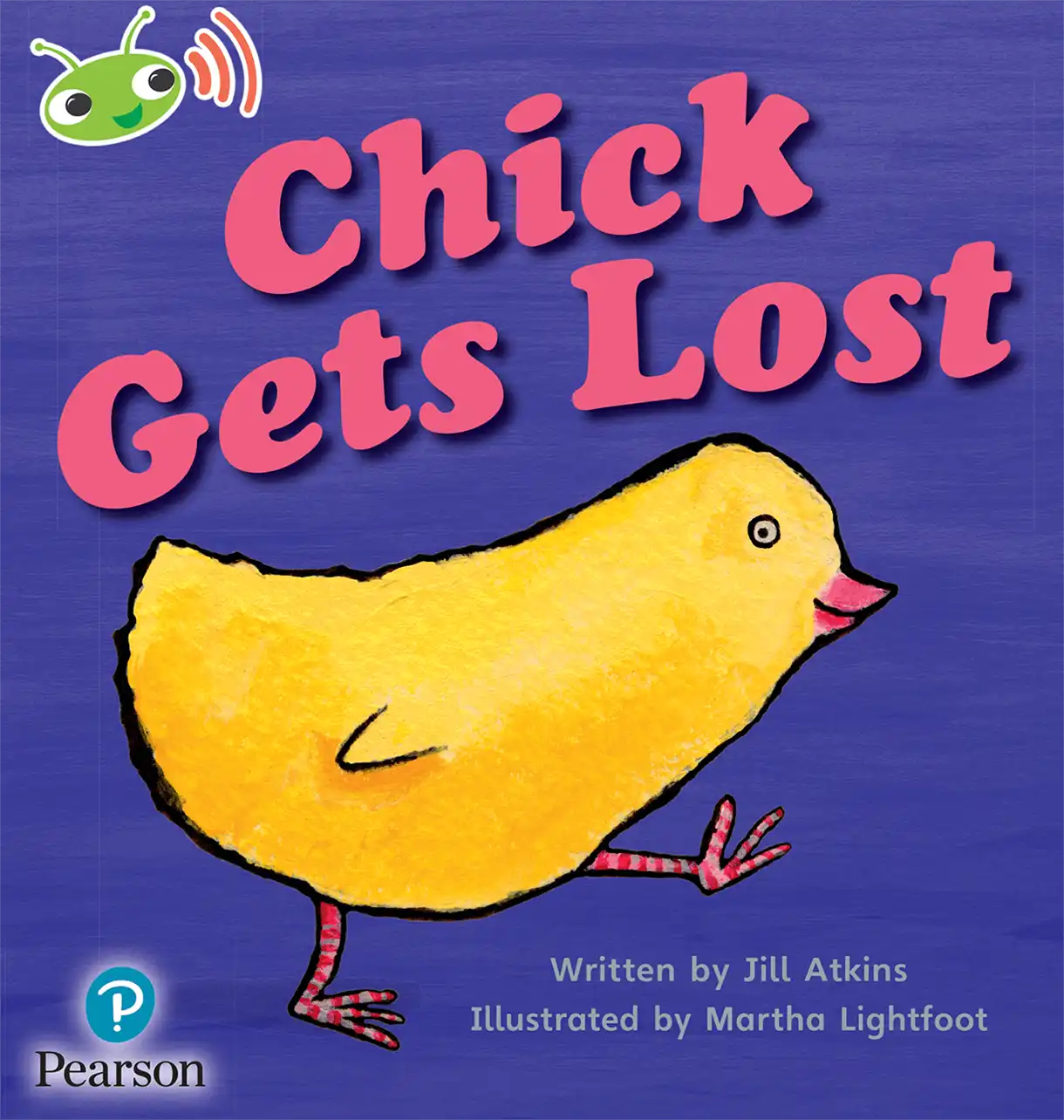

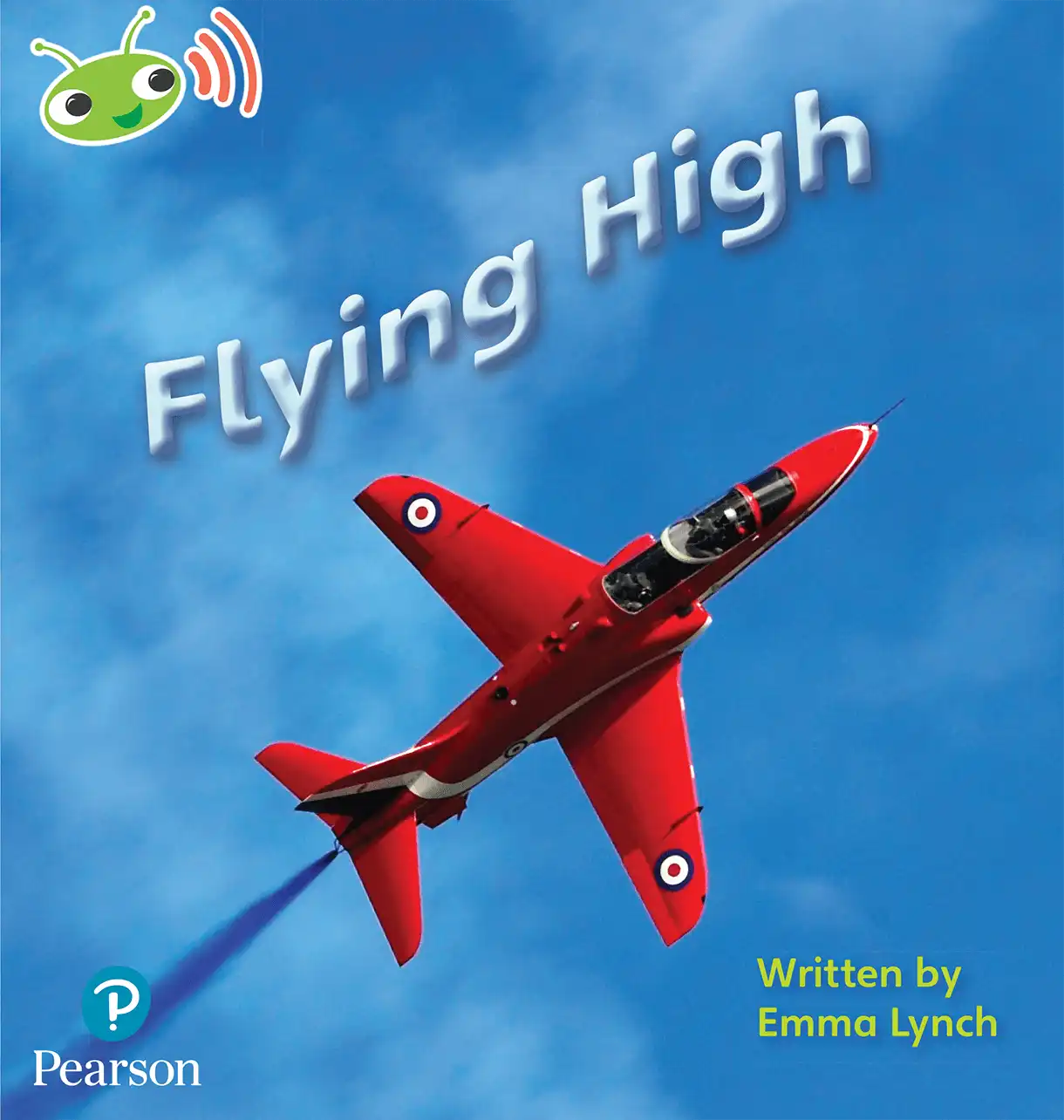

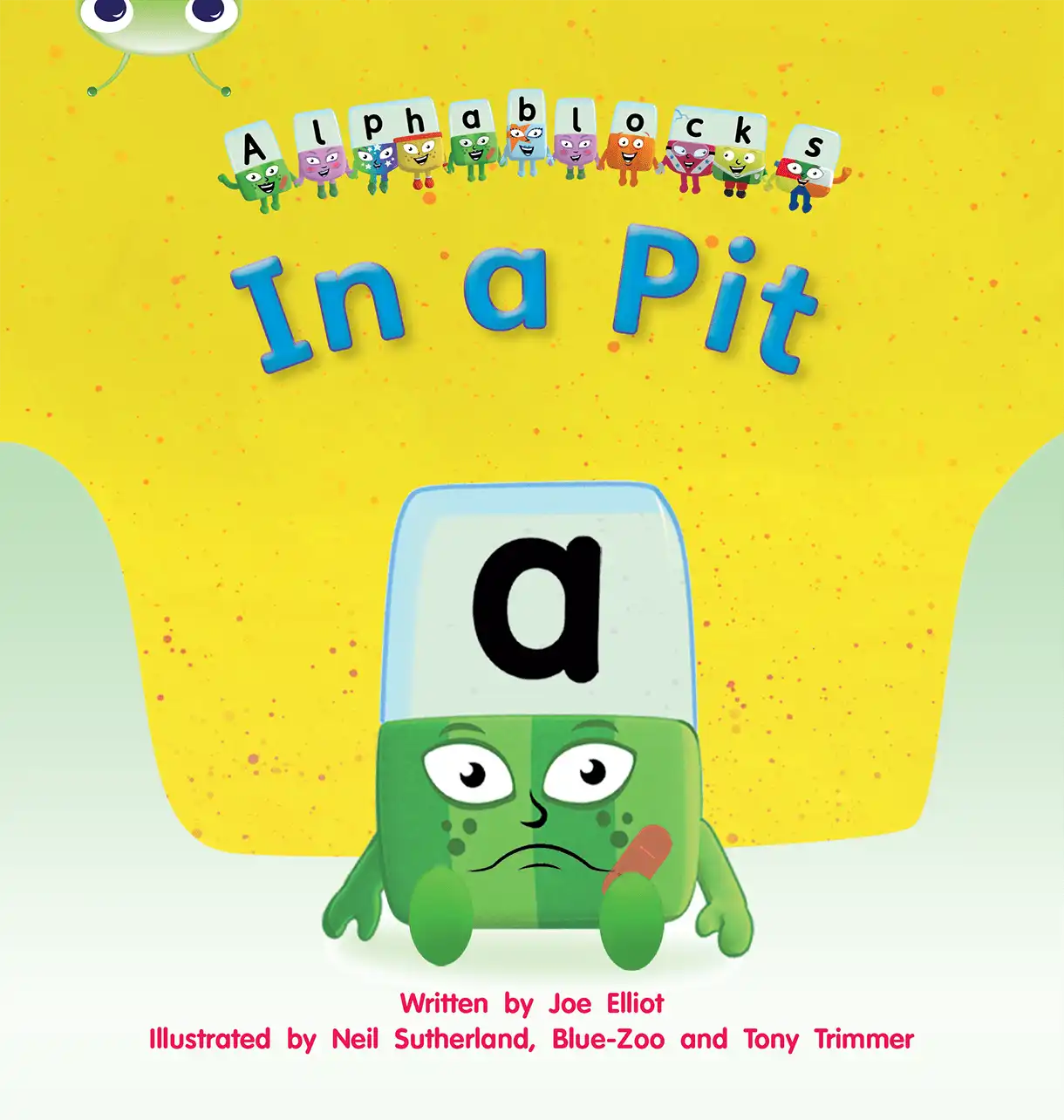

learn to read withmainstream books

Register Now!for up-to-date news aboutRelease Dates

how does it work?