Decoding and Symbols

14 June 2023

When using symbols to support decoding there is definitely a right and wrong way.

Task design demands care and understanding, because when symbols are used incorrectly it can make learning to read more difficult for your students. In this blog I consider how symbol use can impact on the decoding process — the right way to use symbols in decoding tasks, and how we have applied this knowledge in the design of AacapellaRead.

Symbols should only be used in a decoding task when your student already uses symbol-based AAC.

When we use symbols for these students, we are using them to support their expressive language rather than as a decoding aid. The purpose of the symbols is to emulate the process of reading a word out loud once the student has decoded it. This has two important benefits. Firstly, it provides a way for the student to overtly demonstrate that they have correctly decoded the word. Secondly, students find it motivating to be able to demonstrate their knowledge and read out loud like other students. This encourages reading and rereading of texts which is so vital for the development of automatic word recognition and reading fluency.

The decoding process using AAC

Decoding is a skill that allows a student to read words using only the text. A student may read a word by automatically recognising the word, or by using letter-to-sound correspondences to sound out the word. The way we provide symbol supports during this process is critically important.

Let’s start with a simplified flowchart of the reading process that we want students to follow. Then we can look at how we can use symbols, and the impact this has on the learning task.

Imagine that we have presented the student with the word “cat”, and asked them to read the word. The first step in decoding is to look at the word. Once the student has looked at the letters in the word, they will either automatically recognise the word, or will need to sound out the word.

The sounding out process may also be an AAC process depending on needs of the student. The student may mentally sound out the word, or listen to a teacher or other student sounding out the word, and then mentally blend the sounds together to decode the word. Once the student has recognised the word, they will then read the word aloud using AAC. It is at this point in the process that we want to provide students with AAC supports so that they can overtly demonstrate their ability to read the word.

In AacapellaRead we have a complete sounding out process which we will discuss in detail in another blog.

In the flowchart above (and in those that follow), the final AAC process is labelled as 'read word aloud' because this is the process we emulate in AacapellaRead. However, for any student who uses AAC, if they do not use AacapellaRead, this can involve selecting the correct corresponding symbol from an array — with or without voice output from an AAC device. What is important is that we provide an overt method of demonstrating decoding ability without compromising the ability of the student to independently decode the word by embedding words with symbols.

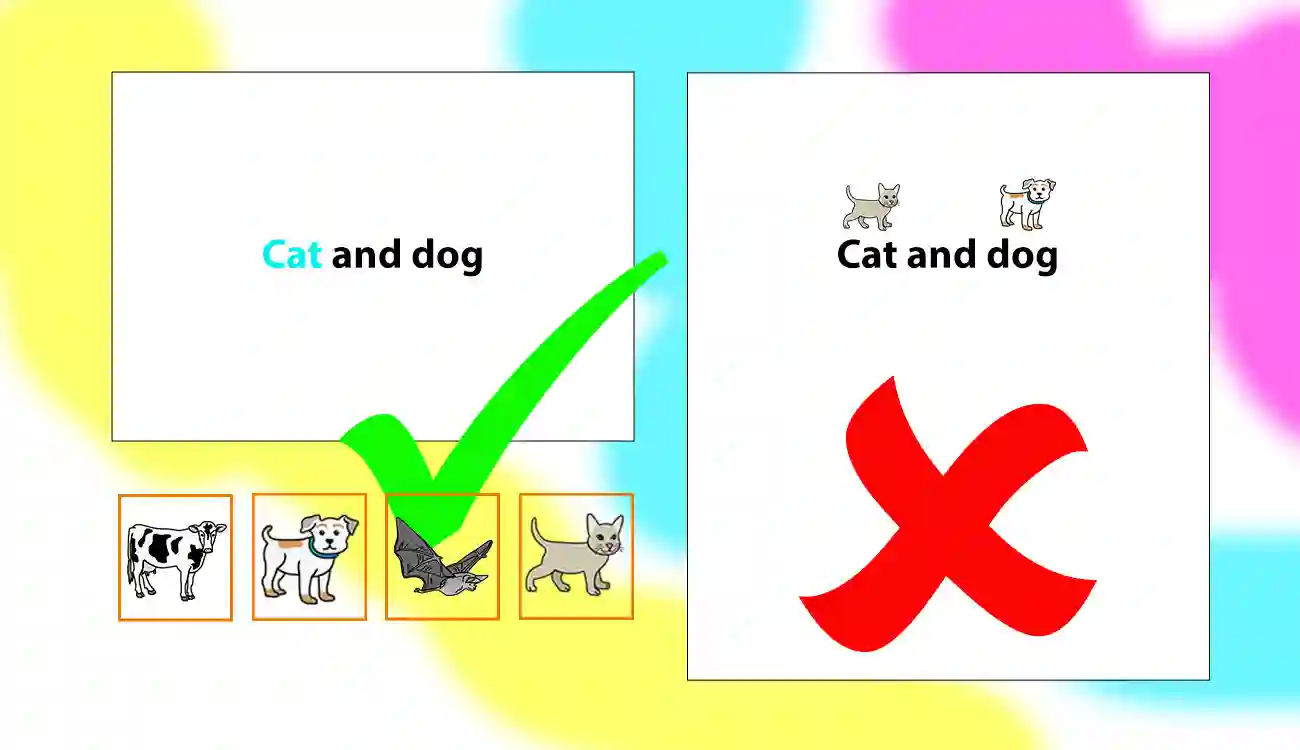

Why not embed the symbols with the text?

Now that we have explored the basic process of decoding, we need to discuss the importance of using symbols correctly. Let's start by exploring what happens when you use embedded text, a practice which is not recommended for the development of decoding skills. The term 'embedded text' describes the practice of presenting the word and the symbol together as a single unit or pair. Typically, this involves the text being placed directly above or below the symbol.

We will use the same word, 'cat', but this time present the word paired with the symbol for cat. The problem with pairing a word with a single symbol is that, if a student recognises the meaning of the symbol such as 'cat', they can totally bypass the decoding process — because they already know the answer without even looking at or sounding out the word.

As you can see from this flowchart, embedding the symbol allows the the AAC process to become the main event rather than a sideshow. The student recognises the word from the symbol and completely bypasses the decoding process. AAC certainly has an important role in learning to decode, but it must only be used as a proxy for speech and not as an alternative method of decoding.

Several studies have shown that pairing symbols with text actually hinders reading progress, as students attend to the picture rather than focusing on the word. Most published research has looked at this problem in the context of learning sight words (words learnt as a chunk). However, for decodable words, symbols are equally likely to distract a student from examining the text and then applying their knowledge of letter-to-sound correspondences to decode the words. When presented with the same text without the embedded symbols, the student is unable to read the words because of their reliance on the symbols.

Our brains are designed to be efficient — if the symbols provided make the need to learn a new process of decoding redundant, then the skill won’t be learnt.

How should we use symbols to assist with decoding?

How do we provide opportunities for students who use symbol-based AAC to overtly demonstrate their knowledge whilst ensuring that they focus on developing their decoding skills? The key is to ensure that the student completes the decoding process before the symbol becomes useful.

There are two important steps to this process. We want to:

- present the text of the word separately from the corresponding symbol.

- present the symbol in an array so that the student must decode and understand the meaning of the word before they can select the corresponding symbol from a choice of symbols.

Using this methodology of matching symbols to words is the preferred method for using symbols during decoding tasks and that is the methodology used in AacapellaRead (see Erickson, Hatch & Clendon, 2010; Fossett & Mirenda, 2006).

Let's revisit the word 'cat'. The student is presented with the word 'cat', and a separate symbol array containing the target symbol and several other symbols. The symbols do not have any text associated with them. The student must attend to the task of decoding the word first because they will only be able to determine the correct symbol when they have decoded the word.

Once the student has decoded the word, they need to recognise and select the corresponding symbol in the symbol array. For this technique to be effective there is a pre-learning task to ensure that students know the meaning of the symbols prior to using them in decoding tasks. In AacapellaRead we have a Learn-It process that helps students to learn a symbol if they do not recognise or remember the corresponding symbol during reading tasks. For the sake of simplicity, this has not been illustrated in the diagram below - we will look in detail at this process in another blog.

In AacapellaRead, when the symbol is selected, voice output reads the word aloud. Alternatively, this task can be completed using symbol selection without voice output.

Decoding in AacapellaRead

This is what the preferred decoding process looks like in AacapellaRead. You can see that the word is displayed using only text in the sentence bar. The symbols are displayed in the grid below the sentence bar below, and there is no text in the grid.

The number of symbol choices displayed to the student can be selected by the teacher. In this case, there are twelve choices in the array (four rows of three), but this can be limited to six (two rows of three), or just three. There is a trade-off here between complexity — more symbols, less guessing, less fluency; and simplicity — fewer symbols, more guessing, better fluency. At Aacapella, we think that an array of six symbols will provide most students with the opportunity to develop fluency, whilst preserving a complexity level that discourages guessing.

Some words cannot be represented semantically by symbols (for example: am, is, was, a, the, be). As is the case in many AAC systems, in AacapellaRead the symbol for these words is the word itself. For these words, although the text is presented separately from the symbol, it is important to recognise that the task is potentially reduced to a match to sample task.

Fortunately, many of these words are considered to be sight words, and, over time, the pairing of the word in the symbol array with the voice output for the word may help with the automatic recognition of these words. The other alternative would have been to create a series of abstract symbols to represent each of these words to ensure true word recognition, but the cognitive load for students was considered too great to justify given that students would only use this symbol set within AacapellaRead.

It is, of course, possible to apply the same principles of symbol use to other low tech and high tech AAC systems. AacapellaRead just makes the task easier by eliminating preparation, maximising reading fluency through our dynamic grid design, and providing students with access to the same high quality readers used by their peers.

Katherine Proudfoot

References

Didden, R., Prinsen, H., & Sigafoos, J. (2000). The blocking effect of pictorial prompts on sight-word reading. Journal of Applied Behavioural Analysis, 33(3), 317-320.

Dittlinger, L. H., & Lerman, D. C. (2011). Further analysis of picture interference when teaching word recognition to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis, 44 (2), 341-349.

Elliott, R. T., & Zhang, Q. (1998). Interference in learning context-dependent words. Educational Psychology, 18 (1), 5-25.

Erickson, K. A., Hatch, P., & Clendon, S. (2010). Literacy, assistive technology, and students with significant disabilities. Focus on Exceptional Children, 42 (5), 1-16.

Fossett, B., & Mirenda, P. (2006). Sight word reading in children with developmental disabilities: A comparison of paired associate and picture-to-text matching instruction. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27, 411-429.

Harzem, P., Lee, I., & Miles, T. R. (1976). The effects of pictures on learning to read. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 46 (3), 318-322.

Hill, L. (1995). An exploratory study to investigate different methods for teaching sight vocabulary to people with learning disabilities of different aetiologies. Down Syndrome: Research and Practice, 3(1), 23-28.

Meadan, H., Stoner, J. B., & Parette, H. P. (2008). Sight word recognition among young children at-risk: Picture-supported vs. word-only. Assistive Technology Outcomes and Benefits, 5(1), 45-58.

Pufpaff, L. A., Blischak, D. M., & Lloyd, L. L (2000). Effects of modified orthography on the identification of printed words. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 105 (1), 14-24.

Samuels, S, J. (1967). Attentional process in reading: The effect of pictures on the acquisition of reading responses. Journal of Educational Psychology, 58 (6), 337-342.

Singer, H., Samuels, S. J., & Spiroff, J. (1973-1974). The effect of pictures and contextual conditions on learning responses to printed words. Reading Research Quarterly, 9 (4), 555-567.

Singh, N. N., & Solman, R. T. (1990). A stimulus control analysis of the picture-word problem in children who are mentally retarded: The blocking effect. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 23 (4), 525-532

Solman, R. T., Singh, N. N., & Kehoe, E. J. (1992). Pictures block the learning of sightwords. Educational Psychology, 12(2), 143-153.

Solman, R. T., & Wu, H. -M., (1995). Pictures as feedback in single word learning. Educational Psychology, 15 (3), 227-244.

Wu, H. -M., & Solman, R.T. (1993). Effective use of pictures as extra stimulus prompts. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 63, 144-160.

Katherine Proudfoot